How To Talk To Your Kids About Tragedy. Thankfully, the most vivid memories that I have of the past tend to be the happy ones, joyful moments. Unfortunately, I also vividly remember September 9, 2011. We were at The Todd’s family cottage in Maine, and the twins were babies. The TV was on constantly until I finally made everyone mute the sound so I could bring in the boys and get them to bed. When the airports opened again, MacLeanie toddled unsteadily up to one of the National Guardsmen lining the concourse and tapped at his machine gun in a thoughtful sort of way. The soldier was very polite as I seized my boy and backed away with an apology. But the scene of that moment, my baby son standing next to a soldier with an AK-47 just floored me.

In the years since, that image is no longer unusual, or even shocking. the galactic tide of terrorism floods every country with misery and lost lives. Civilian gun violence- nothing to even do with terrorism is up as well. The horrifying loss of 50 people (at press time) and another 53 wounded- most in critical condition- at an Orlando nightclub last Saturday is the a heartbreaking example.

So, the question is this: how do we speak to our children about violence? Avoiding it isn’t as easy as it was on 9.11 when I made them turn down the volume. Children hear and see so much more than we can possibly imagine, and without an explanation, they’re left to interpret it themselves, and that must be terrifying. If you’re struggling with how to explain the…well, the unexplainable cruelty and violence, here’s some suggestions from experts.

We can’t control the actions of the evil and mentally ill, but we can control how the news is presented to our children and help them process it. I picked up a book from Dr. Paul Coleman called “How To Say It To Your Child When Bad Things Happen.” The books has five simple guidelines to work from, I thought it was worth repeating here.

How To Talk To Your Kids About Tragedy

1. Wait until they’re older. Until around age 7, Dr. Coleman suggests only addressing the tough stuff if kids bring it up first. “They might see it on TV or hear about it at school (or heaven forbid even witness it), and then you have to deal with it. But younger children might not be able to handle it well,” says Dr. Coleman.

2. Keep it black and white. Yes, the world can be a cruel place, but little kids, well, can’t handle the truth.”Younger kids need to be reassured that this isn’t happening to them and won’t happen to them,” says Dr. Coleman. Parents may feel like they’re lying, since no one can ever be 100% sure of what the future holds, but probability estimates are not something small kids can grasp, and won’t comfort them.

3. Ask questions. Don’t assume you know how they feel. Instead, get at their understanding of what happened. “They might be afraid — or just curious. You have to ascertain that by asking things like ‘What did you hear? What do you think?'” says Dr. Coleman. “If they are scared, ask what they’re afraid of – don’t assume you know. They could be using twisted logic, like they see a building collapse on TV and think it’s Mommy’s office building. Correct any misconceptions, and then offer assurance.”

4. Don’t label feelings as wrong. Let them know that their feelings make sense, and that it’s ok to feel whatever they’re feeling. Never make them feel bad about being scared.

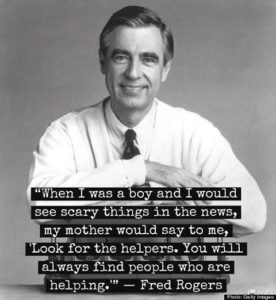

5. Use it as a teaching moment. Talking about bad things can lead to discussions about how to help others, and gives parents an opportunity to model compassion. Talk about donating to a relief organization, or make the message even more personal. “You can say, ‘It makes me think of Mrs. Smith in a wheelchair down the road – maybe we should make her a pot roast,'” says Dr. Coleman.

When Tragedy Affects Someone Your Kids Know

Sometimes tragedy strikes closer to home, and there’s no way to shield your kids. If you’re dealing with the death of a friend or family member, be truthful about it, but offer some separation between what happened and what they fear might happen. “Say ‘Grandma was very old and very sick, but I’m not,'” says Dr. Coleman. “Distinguish yourself clearly from that person so your child can rest comfortably knowing Mommy’s not going anywhere.”